Encountering Anthony Christian

- The Courtauldian

- Aug 7, 2023

- 8 min read

by Sarah Rodriguez | 25 March 2023

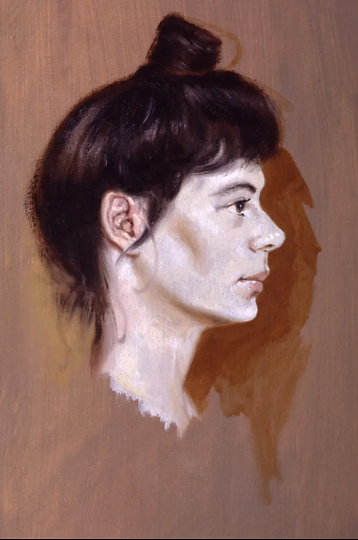

According to Anthony Christian, Art with a capital A is dead, or—at the least—about to die. And still, the seventy-eight-year-old’s drawings and paintings are lucid, distinctive, tension-ridden; they—like the man —teem with life. The moment a piece is “more[so] the result of the brain than the soul” is the moment it is “no longer great Art,” Christian writes from his current home in Leeds, via email. “Thus,” he goes on, almost soliloquizing, “my intolerant attitude to modern art, [which is] the product almost exclusively of man’s ego…” Christian could well be gesturing toward “modern” art as exemplified by Marcel Duchamp here; for the Frenchman famously rejected “retinal” works—those for the enjoyment of the eyes—in favour of those appealing to ideas. In any case, Christian’s life diverges from the course many of his twentieth and twenty-first-century contemporaries have followed. The Brit spent his teenage years as a copyist of the Great Masters; periodically, dedicating himself to the practice of draughtsmanship—the craft of drawing. His has been a disciplined life, moored by artmaking and classical training. But it has also been a bohemian life, with Christian wandering about the world, intermittently struggling to survive and gain visibility. It remains something of a mystery, as to how the artist has yet to receive due recognition—especially to me, as a 2023 Master’s student, here at the Courtauld Institute. ~ Christian’s genesis as an artist began at an astonishingly young age. From three, he studied the works of Old Masters in a set of books called The World’s Greatest Paintings. By ten, it was obvious to all in his vicinity that Christian had a vocation as a creative. Despite growing up in humble and turbulent circumstances, also at age ten, he earned the privilege of copying at London’s National Gallery, breaking precedent with a policy that permitted only students over eighteen to do so. Five years of intense training followed. During the same period, Christian spent time studying anatomy at the Victoria & Albert Museum, where he investigated under the guidance of curator Charles Gibbs-Smith. In his effervescent and sprawling memoir, Art and Soul, Christian asserts that it felt as if he had no choice; “museums,” he writes, “were a necessary part of my life…as a swimming pool would be to an Olympic swimmer…” By way of copying, Christian communed with great artists of the past—notable among them: Da Vinci, Rubens, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt. Under the spell of these Old Masters, he developed a highly critical, exacting eye, formed entirely by the masterpieces in his midst; this paired with the evolution of an “inner voice,” a conscience that would judge all he has ever generated. These doubled as years of abandonment. Due to an unstable family life, the artist left home at twelve, receiving the rest of his education in the National Gallery and on the streets. He earned a living doing odd jobs: from “singing on street corners to washing dishes, from being a butcher’s assistant to working in an office…” “Those years,” Christian writes, with a surprising zest, in his memoir, “are a complete blur to me now”; “days and months all merge together like fruit in a blender, only a little less pleasant as there are too many sad memories of losing friends I cared for, even lovers, always to the same governor of my life—study.” ~ Christian would spend equally formative years in Paris, influenced by Old Masters and Impressionists alike, literally mingling with esteemed artists from Picasso to Dalí. Rooted in classical training, Christian’s epic life and art are, nonetheless, veritably unorthodox. He has trotted the globe, besides Paris, living in New York, Rome, Geneva, Bali, Ibiza, Kodaikanal, and Rajasthan; in addition, he has experimented with eroticism in his creations, not to mention colour and technique, drawing upon but also rebelling against his heroes. Shifting between celebrity status and obscure recluse, Christian has not yet found his place in the canon of art history. Lack of quality or prodigiousness are no matter. A challenging life and his reluctance to conceive of the artist as a producer of consumer goods may in part be responsible. So too, his insistence that invention for its own sake is foolishly glorified—at worst, an impediment to the imbuing of soul into works of art. On and off throughout his life, Christian has battled, on the one hand, a financial imperative to turn his work into a fine-tuned commercial enterprise and, on the other, an obstinate puritanism—operating outside standard art-market logics, following a desire to work wholly in service to his “inner voice.” Sometimes the latter tendency has left him hungry, hardly sheltered, or lacking visibility—as he was in Rome during his early twenties, trying and failing to find collectors for his art. This tendency to serve his inner voice has sometimes allowed him to showcase his art in unusual and accessible venues, available to all, not just those with hefty wallets—as with the creation, in his forties, of a special museum to display his work, called the “Ichor,” in Bali. One such painting, exhibited there, is a profile of a young woman. Her skin, rendered like porcelain, artfully brushes into the backdrop, then disappears. Dark brown hair is swirled up in a high bun, framed by a fringe and a few stray hairs playing by the ear and back of neck. Her jaw line is sleek, and as with her eyes—one third of the way down the head—in perfect anatomical proportion. A shadow behind her face, cast in caramel brown, finds relief against a paler wood-like tint. A Rembrandt-esque interiority is palpable, by way of carefully executed eye colouration. Her gaze at once exudes concentration, elusiveness, and a sense of no-nonsense.

...In Monochrome; oil on canvas; San Francisco, 1981, 10 x 10 ins. (40.5 x 25.5 cms.) (Collection Ichor) Another classically inspired work of art by Christian, forged with great fidelity to his predecessors, is the following charged battle scene. The pieces I’ve chosen simply scratch the surface of his oeuvre; his drawings once caught the attention, too, of Courtauld Professor Sir Anthony Blunt, who, Christian relays, was keen to exhibit a collection of them, but was at the time unable, living in Morocco.

The Battle of Anghiari, a copy of the Rubens’ copy of the (lost Leonardo); New York, 1985, 22 x 29 ins. (56 x 74 cms) ~ During the ‘70s, Christian paid particular attention to his practice of portraiture—one of his primary muses being his second wife, Susan. Simultaneously, he grew ever more fascinated by cloths and fabrics. It’s no surprise, then, that his drawings of these textures ascended to new acmes. His success also earned him widespread recognition (albeit, disproportionately, outside of England) as well as financial flourishing, however temporary. Below, find Susan, drawn with her head pivoted away from the viewer, for reasons we know not. Her hair—enveloped, covered in a turban, heaped high; it’s silken fabric coiled, and on the top, tied. An immediate, haptic, and timeless quality lingers about the fabric. The elegant curvature of the woman’s neck remains exposed, her cheekbone pronounced; from her ear, a single glass-bead earring dangles. The wrinkled, scrunched fabric of the turban contrasts with her smooth, ceramic-like skin. All is connected in an effortless, sinuous line.

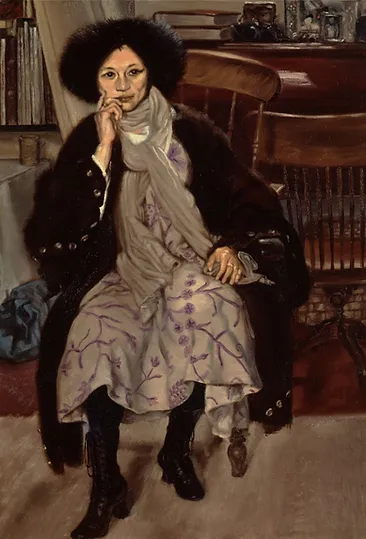

Susan Backview, in a Turban; charcoal pencil, heightened with white chalk on tinted paper; Geneva, 1977, 16 x 11 ins. (40 x 28 cms.) (Collection Ichor) Christian’s portraits of Susan in the 1970s were also inflected by practices he discovered—and to some degree, built upon—in Paris, a city in which he’d spent years immersed. During this time, his work drew more directly upon Impressionist influences—particularly, Degas and Lautrec. As it happens, Christian’s style and technique is perhaps closer to the Impressionists, on the whole, than to the Old Masters’. While his art resembles the latter in its minute detail and high finish, it mirrors the former in its method, its process. Indeed, Christian paints directly, often onto wet canvas, working with great spontaneity and swiftness. He often tries to complete a painting while still “under the spell” of his subject; in this state of “high stimulation,” “almost trance like,” his excitement and love of his subject are translated onto the canvas. Christian’s 1979 portrait, Susan, Paris, offers a case in point of such practices—a piece tinged by Impressionist influences, but also appearing to emanate a distinctively contemporary air. While the artist’s work is inspired by that of the Old Masters and Impressionists, it is not merely a pastiche of these; in his own view, his work is—critically—a continuation of those prior movement’s Spiritual Energy. Its essence is charged with life in new ways. Outfitted in a bohemian dress, Susan strikes a powerful posture, taking up space, her eyes directly piercing those of the artist or appreciator. Her gaze, then, is endowed with unique agency—the fitting output of a self-declared “feminist,” and inhabitant of the twenty-first century.

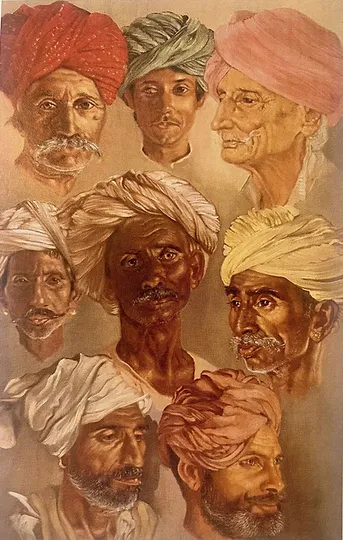

Susan, Paris; oil on canvas; Paris, 1979, 33 x 23 ins. (84 x 53.5 cms) (Collection Ichor) ~ Around the time of this painting, Christian revealed that he was finally able to adequately “express himself.” In the ever-evolving artist’s words, this meant that he would now be able to share, with all those who championed his work, “the awe and joy he felt before all he beheld in which he found beauty and God.” Such an impulse is, by Christian’s own lights, spiritual—and unquestionably so. It is enmeshed, moreover, with a process that has proceeded for roughly 700 years. Indeed, the “canon” of Western art, Christian posits, was sparked by “the Energy” in the 1300s in Italy. Not far after, another eruption emerged, in Flanders—the two movements instituting the Italian and Northern Renaissances, respectively. The church sponsored much of the art at the time; the sheer greatness of the artists implicated, however, quite often transcended “deadening propaganda.” One can, Christian writes, learn to see beyond their “ties to religious institutions,” and see the real “validity” and “marvels” of their works. Eventually, in the late 1500s, Christian continues, other areas of wealth started appearing, and Art was commissioned on a more personal basis, from portraits to genre subjects. Even further down the line, after having passed through periods known as Baroque, Neoclassicism, Rococo, and Romanticism, the Impressionists emerged. From the mid 1800s onward, then, artists began saying, for the first time, “Fuck you, I will paint whatever I like however I want to paint it…” Many “wonders,” Christian writes, were then created; nevertheless, “a new danger appeared.” The Spiritual Energy that had created the past few centuries’ great art, in spite of the church and academic protocol, was becoming more intellectual than spiritual. This process continued, he claims, exponentially—to the point that Art has now become an almost entirely intellectual entity. Thus, Art as “we” know it, of a piece with the roughly 700 year Western canon, is dead or dying, thinks Christian. Of course, whether or not an ossified canon ever existed is itself a contested question; for Christian, though, the canon has been a weighty leviathan, palpably living. And yet, art in some primal form will never die, Christian writes, qualifying his original position. As long as people feel, want to express that feeling, and strive to create beauty, art lives on. It is the canon that will come to an end, and a new art will—perhaps already has—emerged. Is Christian the last of the old guard of spiritual art? Where in this story of Western Art does his work belong? Will his country recognize his oeuvre, as he so desires; will it receive a homecoming, in his lifetime? ~ Among Christian’s art I find most striking is a collection of his pieces from his travels in India. In 1985, the wandering artist found himself in Rajasthan, a state in the northern area. There, he continued to paint, with a particular emphasis on portraiture—which, over the course of his life, has perhaps become his predominant form. In one such work of art of the period, the faces of eight men in turbans gaze at and away from the viewer. The facial hair and forehead of each is rendered singular; their headpieces, tinted a distinctive colour. The intricacy of fold and wrinkle in fabric is at once shockingly realistic and poignantly expressive. In the flicker of each eye, more life is evinced than the intellect can grasp. Art is soul in Anthony Christian’s canvas.

Studies of Indian Heads, Rajasthan; oil on canvas; Jaipur, 1985, 34 x 20 ins. (86 x 61 cms.) (Private Collection, U.K.)

Kik usernames enable vibrant, interest-driven communities, while addressing harmful labels like Kik whores sparks vital dialogues on digital respect. Kik’s group guidelines and user-driven moderation empower collective accountability, turning challenges into momentum for education. By championing empathy and self-policing, these spaces model how tech can evolve through solidarity, fostering inclusive networks where dignity and creativity flourish

Anthony Christian's ability to capture such intricate details is truly mesmerizing—this portrait sounds like a masterpiece of both precision and emotion. The description of her elegant updo and the soft stray hairs evokes a timeless sophistication. For anyone inspired to recreate such classic elegance, exploring hairstyles for women at a professional salon can help you find a style that blends artistry and modern charm.